‘I thought of a suppressed country and a free world.’

‘If we travel from one to another, what will that road look like?’

‘What colours, music there will be? What kind of people would you see?’

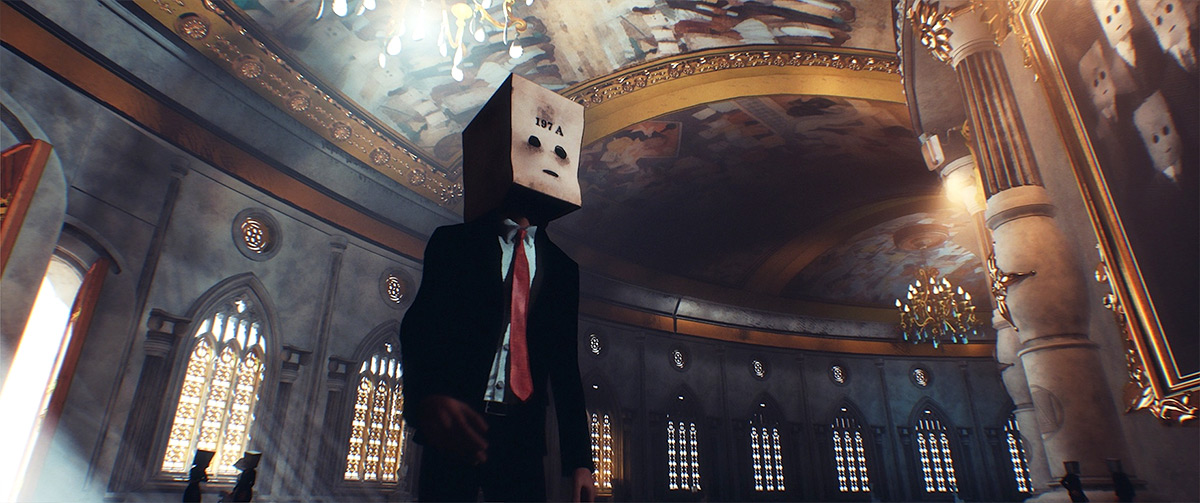

IMAGE: A scene from the animated short film Schirkoa: In Lies We Trust.

An Indian animation film made big news at the International Film Festival of Rotterdam.

Ishan Shukla‘s first feature Schirkoa: In Lies We Trust won the festival’s NETPAC (Network for the Promotion of Asian Cinema) award.

Earlier, in 2016, Shukla had made a 14-minute short by the same name, which won over 30 international awards and was sort of a calling card for his feature film. He also wrote and directed the short Star Wars: Vision, Volume 2, the animated Star Wars anthology steaming on Disney+.

A visually stunning, dystopian sci-fi thriller, Schirkoa: In Lies We Trust is an imaginative and colourful film.

In Schirkoa, the world imagined by Shukla, men and women have their heads covered with paper bags. All bagheads look alike. No one has an individual personality.

Each person is given a name: A number, followed by an alphabet.

There is a kingdom called Konthaqa, where a rebellious group of immigrants live, each with a unique look and personality. From the complete control of the society in Schirkoa, we move to the totally free Konthaqa.

In keeping with the international nature of Schirkoa and Konthaqa, Shukla has cast an array of actors from different countries, who lend their voices to the film’s characters, including actors Golshifteh Farahani (Iran), Asia Argento (Italy) and film-makers Gasper Noé (Argentina), Lav Diaz (Philippines). There are voices of Indian filmmakers too, like Shekhar Kapur, Anurag Kashyap and Karan Johar.

The film’s music is composed by Sneha Khanwalkar.

The director is currently based in a Swaminarayan monastery in Vadodara, Gujarat, where he helped set up an animation studio. He works with the monks to spread their message through spiritual animation and music.

In a Zoom conversation with Aseem Chhabra, Shukla says, “What if we go to the extreme level of freedom and suppression, eventually will any of these civilisations be livable or not? That was the ultimate idea that became Schirkoa.”

IMAGE: A scene from the animated short film, Schirkoa: In Lies We Trust.

Ishan, I loved your film. I don’t usually rush to animation. But this was animation with such creative ideas. There are so many layers of stories.

I read that you have been making comics since you were a kid. Where did that fascination come from?

Since a very early age, I was seeing my father acting.

He was a theatre artist in Bhopal.

I would play in the corner when he would be rehearsing, say a Samuel Beckett play.

I would hear very big, intellectual things, which I would not really understand.

My mother is a writer and a teacher. I would see her manuscripts lying around. That was really my upbringing.

What are your parents’ names?

My father’s name is Dev Kant Shukla and my mother’s name is Vandhana Shukla. They used to act together.

They had a theatre group in Gwalior and later in Bhopal.

We had a lot of books lying around.

Of course, I had Chandamama and Champak, but I would find Khalil Gibran because my father was reading him.

By the age of 9 or 10, I was reading Khalil Gibran and Tolstoy, even though I would not understand them fully.

But I would ask questions.

Then, I would try to mimic them in comics, which were not like Diamond or Indrajal comics. I was trying to create something which was slightly different, more adult like world in comics.

I had no idea that graphic novels existed.

But I was trying to do that kind of a thing initially as a kid.

Thankfully, I was good at drawing.

I never liked school. So for me, coming back from school and working on my comics for two-three hours every day was my play. All through my early childhood, I would be itching to come back home and draw something.

I would always think what my next character is doing.

What is happening in this world?

Funnily enough, when I was nine years old, I wrote a comic and its name was Schirkoa. It was a fictitious world.

That time, the story was completely different but that name stuck.

I used that name even later because I thought it was cool and a homage to my nine-year-old self.

IMAGE: A scene from Schirkoa: In Lies We Trust.

What does Schirkoa mean?

It’s a gibberish blabber of a nine-year-old kid. Nothing more than that.

The idea of bagheads and the anti-immigrant hysteria that we see in America and Europe, how did you decide to put that together with the two separate worlds, Schirkoa and Konthaqa?

I started my career in Singapore; I was working there as an animator.

I was excited to work in this creative industry. But after a few months, I realised it’s just another grind, another cubicle.

At the end, I was just working on a computer like any other person in the world, and that is where my dreams kind of shattered.

I got back to my diary. I would carry it every time and would draw it in it.

I was going in a subway every day, commuting to office for 45-50 minutes and I realised that I was becoming a very replaceable person in this world. Because you see this office-going crowd with glum faces glued to their mobile screens all the time and you realise that you can basically be anywhere.

One day I saw my reflection in the train mirror. I just drew myself, but instead of my face, I drew a box. That drawing, plus the Orwellian thought that you are just a cog in the wheel of the daily grind and somebody is suppressing you, was the initial idea.

Then I also started noticing the world around me. Arab Spring happened.

Things in Hong Kong and Yemen happened.

Things are happening in India.

Every time when something happened, it reinforced the idea that perhaps it can go a little deeper than an intellectual dystopia of a person, who is losing his individuality. It’s the civilisation itself, which is losing its individuality.

So then I tried to go beyond that.

What if all these exiles who don’t abide by those rules create their own country?

There they can have absolute freedom, with no order whatsoever.

I wanted to make sure I was showing the absolutes of the spectrum.

No gray areas.

Absolute suppression and absolute freedom.

What if we go to the extreme level of freedom and suppression, eventually will any of these civilisations be livable or not? That was the ultimate idea that became Schirkoa.

IMAGE: A scene from Schirkoa: In Lies We Trust.

But what you do is so creative. It’s a thriller, but more than that. There’s a sequence in the short, as well as in the feature film where the protagonist, who is named 197 A, goes on the scooter with the woman 33 F, who has wings.

That scooter ride itself was so thrilling, like a chase sequence in a James Bond film. Or that bus ride, which is so imaginative, just wild, colourful fun. What inspired those scenes?

I spent a lot of time in Rajasthan.

I was with my mother and brother living there.

Later, I studied at BITS Pilani.

I would see a lot of gypsies who would dance, live there for a while and then disappear. They would wear the most colourful clothes.

Their faces would be so unique.

You would see them if you traveled in the interiors of Rajasthan and in the roadway buses.

The buses were very intricately detailed, but it felt like they would shatter apart at any point. And there were no real roads.

I was always juxtaposing fantasy over it, even as a 10-12-year-old kid.

I never saw the gypsies as gypsies. I always saw them as larger-than-life, free people.

So I thought of a suppressed country and a free world. If we travel from one to another, what will that road look like? What colours, music there will be? What kind of people would you see?

My Chinese designer, Yaning Feng, and I came up with these wonderful characters.

We started jamming together.

That bus journey is basically a complete segue from what we expect from this film.

Everyone expects a baghead country, a dystopian Orwellian mythology and then we just take a complete segue into this world that nobody has ever seen before.

I was also inspired by (Chilian film-maker) Alejandro Jodorowsky and the images he created in his classic film The Holy Mountain (1973). He has also written a few graphic novels.

Musically, Sneha and I sat together to try to find out what kind of sounds we would hear on that bus ride.

Ultimately, we decided it cannot be one melody, one instrument. It has to be absolute chaos.

Obviously this is not India that you have created, but your opening shot is outside of a bar called Sharab, which keeps re-appearing. Then you have Gasper Noé’s voice and a top shot of different rooms in a brothel. That was homage to Gasper’s film Enter the Void, right?&

I am glad that you noticed that. It’s definitely homage to Enter the Void.

I love that movie.

I love the way he showed the Japanese brothel. It was fascinating.

IMAGE: Director Ishan Shukla who made Schirkoa: In Lies We Trust. Photograph: Kind courtesy Ishan Shukla/Instagram

I also saw a lot of Blade Runner in the imagery. Any other films or animation styles that inspired you?

Blade Runner happened accidentally.

My real inspiration for the blue district area in Schirkoa came from a lot of Southeast Asian countries, the night culture there, the neon signs, and the lit-up streets.

I love Blade Runner, but was not aiming for it.

As I got more and more Southeast Asian references and the bars, the street scenes, it slowly became Blade Runnerish in a way.

Another reference that comes to my mind are video games. I play a lot of video games, and am extremely inspired by the art they do.

There was a popular series called Bioshock that inspired me in just the world-building aspect. The whole city exists under water in America.

Finally, tell us about the casting, getting all these voiceover artists from Golshifteh to Asia, Lav Diaz, Gasper Noé, Shekhar Kapur, Anurag Kashyap, even Karan Johar.

I knew I was making an international film.

It’s not just in English, but it’s a sandbox in which anybody from any part of the world can come and bring in their artistic sensibilities.

Schirkoa is a concentration of multiculturalism, all the ethnicities, cultures, languages can thrive there.

My French producer mentioned a couple of names which were completely out of the box.

The top two names were Gasper Noé and Lav Diaz. I asked, how do we fit them in? She said, let’s approach them first. We send them the visuals and the script, and to our surprise, both of them agreed.

Then we approached Golshifteh and the French singer Soko.

It’s not just that they are great actors but they are physical embodiment of these characters.

Golshifteh lives in exile in France and sang a Persian song in the film, which was not in the script, but she suggested it.

Asia’s name was suggested by Stephan Holl, my German co-producer. When Asia read the script, she seemed to know what to do with her character.

She said, ‘Just give me a cigarette and I know what to do.’

My producer suggested Canadian German musician King Khan, who was born in Uttar Pradesh. His family first migrated to Canada and then to Germany. He works with Sun Ra Arkestra and they create this wonderful otherworldly music. We licensed three tracks from him.

I have loved Piyush Mishra’s voice and poetry since I saw him perform in Gwalior. I used one of his poems and got him to recite it in the film.

My Indian producer Samir Sarkar suggested Shekhar Kapur because he has an older voice.

After that, we approached Anurag Kashyap.

Samir and Anurag than asked if I would consider Karan.

At that point, it was a bit jarring for me. I never imagined him in a project like this.

But then I realised he would be perfect as a TV, radio host and an announcer. Actually, what he speaks is quite dark. But he speaks in a flamboyant style which makes it quite ironic. And he really enjoyed doing it.